7 Proven Nonprofit Strategic Plan Example Frameworks for 2026

Explore our curated nonprofit strategic plan example collection. Find 7 actionable frameworks with analysis and tips to strengthen your grant proposals.

A powerful strategic plan is more than a document; it's a roadmap to impact and a critical tool for securing funding. Yet, many nonprofits struggle to move from abstract mission statements to a concrete plan that energizes staff and impresses funders. This common challenge often results in plans that gather dust on a shelf rather than driving action. The disconnect between planning and execution can stall growth and jeopardize essential funding opportunities.

This guide cuts through the complexity. We've compiled a curated collection of diverse, real-world nonprofit strategic plan example frameworks, each tailored for different organizational needs. We will break down the strategic DNA of each model, from the rigorous Theory of Change beloved by foundations to the agile OKR system favored by innovators. This is not another collection of generic templates; it's a practical toolkit for building a plan that works.

Inside, you will find a deep analysis of each example, complete with annotated strengths, potential weaknesses, and explicit guidance on how to adapt these frameworks to win grants, even with limited capacity. We will show you precisely how to leverage these models to articulate your vision, demonstrate your competence, and build a compelling case for investment. By the end of this article, you will have the insights needed to select and implement a strategic planning process that aligns your team, clarifies your impact, and convinces funders you are an organization worthy of their support.

1. Theory of Change (ToC) Strategic Plan Template

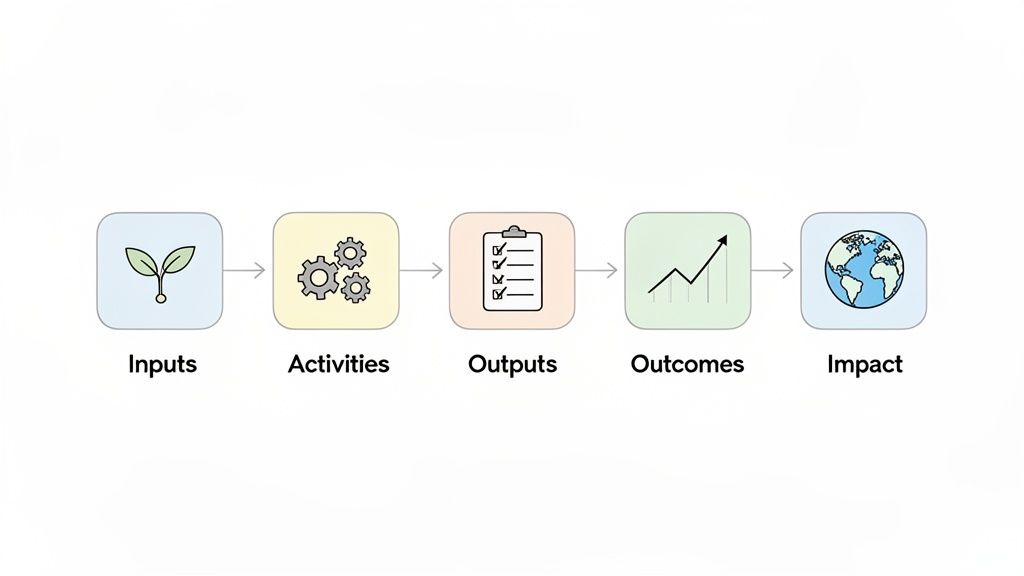

A Theory of Change (ToC) is less a rigid template and more a dynamic framework that provides the foundational logic for your nonprofit's strategy. It visually and narratively explains the "how" and "why" behind your work, mapping the complete journey from your available resources (inputs) to your ultimate, long-term goal (impact). This approach forces your team to articulate and test the assumptions connecting your day-to-day activities to the large-scale change you aim to create.

Unlike traditional strategic plans that might focus solely on organizational goals, a ToC centers on the causal pathway of social change. It's a powerful tool for aligning your staff, board, and funders around a shared understanding of your mission.

Strategic Analysis & Breakdown

The core strength of the ToC model is its emphasis on causality. It’s not just a list of what you will do; it’s a hypothesis about how change will happen. This makes it an invaluable nonprofit strategic plan example for organizations focused on complex social issues.

Structure: The typical ToC model follows a clear sequence:

- Inputs: Resources you have (staff, funding, facilities).

- Activities: What you do (workshops, counseling, advocacy).

- Outputs: The direct results of your activities (number of people trained, hours of service delivered).

- Outcomes: The specific, measurable changes in your target population (improved skills, increased awareness, changed behaviors).

- Impact: The long-term, systemic change you contribute to (reduced poverty, improved community health).

Key Advantage: The ToC forces you to identify and scrutinize your "assumptions" - the connecting beliefs that bridge each step. For example, you might assume that providing financial literacy workshops (activity) will lead to better household budgeting (outcome). A ToC framework requires you to state this assumption explicitly and plan how to measure if it's true.

Actionable Takeaways & Adaptation

A ToC is especially powerful for grant writing and reporting because it directly answers the questions funders care about most: "What change are you trying to make, and how will you know if you're successful?"

For Grant Applications:

Frame your grant proposal narrative around your Theory of Change. Dedicate a section to explaining your causal pathway, using the ToC as a visual aid. This demonstrates a sophisticated, evidence-based approach to your work.

Pro Tip: When a grant application asks for your "program logic" or "evaluation plan," your ToC is the perfect source material. Directly link your proposed activities to your projected short-term and long-term outcomes, using the language you've already developed.

For Resource-Constrained Nonprofits:

Developing a ToC doesn't require expensive consultants. Start with a simple whiteboard session with your team and key stakeholders. Ask the fundamental question: "What is our ultimate goal?" and then work backward, step by step, asking "What needs to happen before that?" for each stage. This collaborative process builds internal alignment and ownership of the strategy.

2. Balanced Scorecard Strategic Plan Model

The Balanced Scorecard is an organizational performance management framework that moves beyond traditional financial metrics to provide a more holistic view of your nonprofit's health. It translates your mission and vision into a comprehensive set of measurable objectives distributed across four key perspectives: Financial, Customer (or Stakeholder/Mission), Internal Processes, and Learning & Growth. This approach ensures your organization doesn't over-focus on one area, like fundraising, at the expense of others, like program quality or staff development.

Unlike plans that only list long-term goals, the Balanced Scorecard creates a "dashboard" of critical indicators. It connects high-level strategy to day-to-day operational tasks, making it a powerful tool for aligning your entire team, from the board to program staff, around a unified set of priorities.

Strategic Analysis & Breakdown

The core strength of the Balanced Scorecard is its emphasis on balance and measurement. It forces leadership to define what success looks like across the entire organization, not just in the finance department. This makes it an excellent nonprofit strategic plan example for organizations seeking to improve operational excellence and demonstrate comprehensive impact.

Structure: The model organizes objectives, metrics, and initiatives into four essential quadrants:

- Financial Perspective: How do we appear to our funders and donors? (Metrics: revenue diversification, fundraising ROI, administrative cost ratio).

- Customer/Stakeholder Perspective: How do our constituents and partners see us? (Metrics: client satisfaction, program enrollment, community engagement).

- Internal Processes Perspective: What business processes must we excel at? (Metrics: program efficiency, grant application success rate, volunteer retention).

- Learning & Growth Perspective: How can we continue to improve and create value? (Metrics: staff training hours, employee satisfaction, system upgrades).

Key Advantage: The framework creates clear, cause-and-effect linkages between the perspectives. For instance, investing in staff training (Learning & Growth) should improve program delivery efficiency (Internal Processes), which leads to better outcomes for clients (Customer/Stakeholder) and ultimately justifies continued funding (Financial).

Actionable Takeaways & Adaptation

A Balanced Scorecard is incredibly effective for board reporting and demonstrating sophisticated management to major donors and institutional funders. It shows you are running your nonprofit like a well-managed, data-driven organization.

For Grant Applications:

Use your Balanced Scorecard as direct evidence of your organization's capacity and commitment to performance management. Include a summary or a visual of your scorecard in your grant proposal's organizational background section to showcase your strategic approach.

Pro Tip: When a grant application asks how you will monitor success, reference specific metrics from your scorecard. For example, "We will track progress toward our goal using our Internal Process metric of 'reducing client intake time by 15%,' which is reviewed quarterly by our leadership team."

For Resource-Constrained Nonprofits:

You don't need complex software to start. Begin with a simple spreadsheet listing 3-4 key objectives and one or two metrics for each of the four perspectives. The goal is to start small and focused, choosing metrics that are truly important, not just easy to measure. This process can be facilitated in-house during a leadership retreat or a series of team meetings to ensure buy-in.

3. Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats (SWOT) Analysis Strategic Plan

A SWOT analysis is a foundational strategic planning framework that helps a nonprofit assess its current position by evaluating internal and external factors. It organizes your thinking into four distinct quadrants: Strengths and Weaknesses (internal factors you can control) and Opportunities and Threats (external factors you cannot control but must respond to). This method provides a clear, high-level snapshot of your organization's strategic landscape.

This framework is highly effective for nonprofits conducting initial strategic planning sessions, annual reviews, or program-specific evaluations. Unlike more complex models, its simplicity allows for broad participation from staff, board members, and even volunteers, ensuring diverse perspectives are included. The resulting analysis directly informs strategic priorities and realistic goal-setting.

Strategic Analysis & Breakdown

The power of a SWOT analysis lies in its ability to synthesize complex information into an organized, actionable format. It bridges the gap between your internal reality and the external environment, making it an essential nonprofit strategic plan example for identifying where to focus limited resources.

Structure: The analysis is built on a simple 2x2 matrix:

- Strengths (Internal): Your organization's advantages. What do you do well? (e.g., strong community reputation, dedicated staff, unique program model).

- Weaknesses (Internal): Areas for improvement. Where are you lacking? (e.g., outdated technology, limited funding diversity, staff burnout).

- Opportunities (External): Favorable external factors you could leverage. What trends can you capitalize on? (e.g., new grant funding, growing community need, favorable policy changes).

- Threats (External): Unfavorable external factors that could harm your mission. What obstacles do you face? (e.g., economic downturn, increased competition, changing regulations).

Key Advantage: A SWOT analysis forces you to be honest about your capabilities while remaining aware of the broader landscape. It helps identify strategic pairings, such as using a key strength to capitalize on an external opportunity or addressing a critical weakness to mitigate an emerging threat.

Actionable Takeaways & Adaptation

The real value of a SWOT analysis is translating the findings into concrete actions. It's a powerful tool for positioning your organization to funders, demonstrating self-awareness and strategic thinking.

For Grant Applications:

Use your SWOT analysis to build a compelling case for support. A well-defined weakness can be framed as a strategic investment opportunity for a funder to help you overcome a challenge and increase your impact.

Pro Tip: Position your grant proposal as a direct response to your SWOT findings. For instance: "Our analysis identified a weakness in our data collection capacity (Weakness) which prevents us from fully demonstrating our impact to stakeholders. This grant will fund a new CRM system, allowing us to capitalize on the growing demand for data-driven outcomes (Opportunity)."

For Resource-Constrained Nonprofits:

A SWOT analysis is an ideal, low-cost strategic planning tool. It can be conducted in a half-day workshop with a facilitator, a whiteboard, and sticky notes. Invite a mix of staff and board members to ensure you capture a 360-degree view of the organization. The insights gathered can form the basis for 3-5 key strategic initiatives for the upcoming year.

The "Opportunities" and "Threats" sections often overlap with the findings from a community needs assessment. A thorough understanding of community needs can reveal significant opportunities for program expansion or threats from shifting demographics. For a deeper dive, you can explore how to write a needs assessment to strengthen your external analysis.

4. Nonprofit Strategic Priorities Matrix (Impact-Feasibility Analysis)

The Strategic Priorities Matrix is a powerful decision-making tool that helps nonprofits focus their limited resources on what matters most. It visually maps potential initiatives on a two-by-two grid, plotting them based on their potential for mission impact versus their organizational feasibility. This framework forces a disciplined conversation about trade-offs, ensuring that strategic choices are intentional, data-informed, and directly tied to your core purpose.

Unlike for-profit models that might prioritize revenue or market share, this matrix explicitly centers mission advancement. It provides a clear, compelling rationale for why certain programs are pursued while others are postponed or redesigned, making it an invaluable tool for transparent communication with your board, staff, and funders.

Strategic Analysis & Breakdown

The core value of the Impact-Feasibility Matrix is its clarity and focus. It moves strategic planning from a long list of "good ideas" to a prioritized action plan. This makes it an essential nonprofit strategic plan example for organizations facing tough choices about resource allocation.

Structure: The matrix is divided into four quadrants:

- High Impact / High Feasibility (Quick Wins): These are top priorities. Pursue them immediately as they offer significant mission return for a manageable level of effort.

- High Impact / Low Feasibility (Major Projects): These are big, transformative goals. They require significant investment, strategic partnerships, or long-term capacity building. They often form the core of major grant proposals.

- Low Impact / High Feasibility (Fill-ins): These activities are easy to do but don't significantly advance the mission. They should be minimized, delegated, or automated to free up resources.

- Low Impact / Low Feasibility (Time Sinks): Avoid these initiatives. They consume precious resources for minimal mission-related gain.

Key Advantage: This model provides a shared language for strategic decision-making. It transforms subjective opinions into an objective framework, helping to build consensus among diverse stakeholders and justify difficult choices, like sunsetting a legacy program that is no longer high-impact.

Actionable Takeaways & Adaptation

The matrix is a perfect tool for developing a targeted fundraising strategy and communicating your needs clearly to grantmakers. It shows you've done the hard work of prioritizing.

For Grant Applications:

Use the matrix to build a compelling case for capacity-building support. Frame your grant narrative around an initiative in the "High Impact, Low Feasibility" quadrant. Explain that your organization has identified a critical, mission-advancing opportunity and needs specific funding to make it feasible.

Pro Tip: When a funder asks about your strategic priorities, share a simplified version of your matrix. This visually demonstrates your strategic thinking and shows them exactly where their investment will unlock the most significant impact. It answers the "why this, why now" question instantly.

For Resource-Constrained Nonprofits:

You can create this matrix in a single team meeting using a whiteboard and sticky notes. First, brainstorm all potential projects and ideas. Next, as a group, define what "impact" (e.g., lives changed, policy influenced) and "feasibility" (e.g., funding, staff time, expertise) mean for your organization. Then, collaboratively place each sticky note on the matrix, discussing its position until you reach a consensus.

5. Nonprofit Strategic Plan Template with Three-Year Rolling Plan

A three-year rolling strategic plan offers a powerful blend of long-term vision and near-term adaptability. This model provides a structured yet flexible framework where the first year is planned in meticulous detail, while the second and third years are outlined with broader goals. Each year, the plan "rolls" forward: the completed year is archived, the current year becomes the new Year 1, and a new Year 3 is added to the horizon.

This dynamic approach prevents the strategic plan from becoming a static document that gathers dust on a shelf. It forces an annual rhythm of reflection, assessment, and forward planning, making it ideal for organizations navigating fluctuating funding streams, evolving community needs, and multi-year grant cycles.

Strategic Analysis & Breakdown

The core value of the rolling plan is its structured agility. It acknowledges that the world can change significantly in three years, allowing nonprofits to pivot without abandoning their core strategic direction. This makes it an essential nonprofit strategic plan example for organizations that need to demonstrate both stability and responsiveness to funders.

Structure: The plan is built on a recurring three-year cycle.

- Year 1 (Implementation Year): Features detailed, specific, and measurable objectives, often broken down quarterly. This includes clear action steps, assigned responsibilities, and defined key performance indicators (KPIs).

- Year 2 (Directional Year): Outlines strategic priorities and goals at a higher level. The specific tactics to achieve them are not yet finalized, allowing for adjustments based on Year 1 outcomes.

- Year 3 (Visionary Year): Focuses on broad, aspirational goals that set the long-term direction for the organization. This year is the most flexible and is shaped by emerging trends and opportunities.

Key Advantage: This model excels at aligning operational activities with funding cycles. The detailed Year 1 plan can be directly tied to current grant deliverables and budgets, while Years 2 and 3 provide the strategic narrative for future grant proposals and long-term donor cultivation.

Actionable Takeaways & Adaptation

A rolling plan is particularly effective for demonstrating strategic foresight to major foundations and institutional funders who often require multi-year plans. It shows you are thinking beyond the current grant cycle.

For Grant Applications:

Use the rolling plan to create a compelling narrative of growth and impact over time. In a grant proposal, present your Year 1 objectives as the specific, funded activities you will undertake. Then, use the goals for Years 2 and 3 to illustrate the project's scalability and long-term vision.

Pro Tip: Create a one-page executive summary of your three-year plan specifically for funders. Use visuals to map how their potential investment in Year 1 activities will help achieve the broader goals laid out in Years 2 and 3.

For Resource-Constrained Nonprofits:

The annual review process is your most critical tool. Schedule a dedicated strategic planning retreat each year to analyze the previous year's performance, refine the upcoming year's plan with concrete details, and add a new visionary Year 3. This ensures the plan remains relevant without requiring a massive overhaul every few years. You must also align your finances with each year's goals; a strong budget example for nonprofit organizations can serve as a template for forecasting your annual operational needs.

6. Logic Model Strategic Planning Framework

A Logic Model is a visual roadmap that illustrates the logical connections between a program's resources and its intended results. Often considered a more linear and program-specific cousin to the Theory of Change, it shows how your inputs and activities will lead to outputs, outcomes, and ultimately, a broader impact. This framework is a standard requirement for many government and foundation grants, forcing nonprofits to clearly define program components and expected achievements.

Unlike a high-level strategic plan that might cover the entire organization, a Logic Model typically zooms in on a single program. This focus provides clarity for program design, management, and evaluation, ensuring that every action is purposefully linked to a measurable result. It's an indispensable tool for demonstrating a well-reasoned and evidence-informed approach to program development.

Strategic Analysis & Breakdown

The core value of a Logic Model is its structured, linear thinking. It moves from "what we invest" to "what we hope to achieve" in a clear, sequential path. This makes it a powerful nonprofit strategic plan example for organizations that need to articulate program specifics to funders like the Department of Health and Human Services or AmeriCorps.

Structure: The Logic Model is typically presented in a table or flowchart format with five core components:

- Inputs/Resources: What you invest (staff time, funding, materials, partnerships).

- Activities: What you do (conduct workshops, provide mentoring, distribute resources).

- Outputs: The direct products of your activities (number of workshops held, number of participants served).

- Outcomes: The changes in participants' knowledge, skills, or behavior (short, medium, and long-term).

- Impact: The ultimate, broader change in the community or system you are contributing to.

Key Advantage: The Logic Model excels at providing clarity and a basis for measurement. By defining specific outputs (e.g., "150 youth will attend our workshop") and outcomes (e.g., "75% of attendees will demonstrate increased knowledge on post-workshop surveys"), it creates a built-in evaluation framework that is easy for funders and stakeholders to understand.

Actionable Takeaways & Adaptation

The structured format of a Logic Model makes it exceptionally useful for grant writing, especially for government applications that demand a high level of detail and a clear plan for evaluation.

For Grant Applications:

Develop a distinct Logic Model for each program for which you are seeking funding. This demonstrates a granular understanding of your work and allows you to tailor your narrative precisely to the funder's priorities. The model itself can often be inserted directly into the proposal as a required attachment.

Pro Tip: Use your Logic Model as a checklist when writing your grant narrative. Ensure every activity you describe is linked to a specific outcome, and that your budget (Inputs) clearly supports your proposed activities. To learn more about this process, explore how to build a logic model for program evaluation in greater detail.

For Resource-Constrained Nonprofits:

A Logic Model is an excellent internal planning tool that requires no special software. Gather your program team with a large piece of paper or a whiteboard and draw five columns for the core components. Start by defining your ultimate goal (Impact) and work backward, or start with your resources (Inputs) and work forward. This process helps ensure your entire team is aligned on program goals and how they will be achieved.

7. OKRs (Objectives and Key Results) Strategic Planning Framework

Originating in the tech sector and popularized by John Doerr, the Objectives and Key Results (OKRs) framework is an agile, goal-setting methodology gaining traction in the nonprofit world. It provides a simple yet powerful way to set ambitious, measurable goals on a quarterly basis, fostering both focus and flexibility. An Objective is a qualitative, aspirational goal that answers, "Where do we want to go?" while Key Results are the quantitative, measurable metrics that answer, "How will we know we're getting there?"

Unlike traditional annual strategic plans that can become static, OKRs are designed for rapid iteration and adaptation. This framework shifts the focus from a long list of activities to a handful of critical outcomes, making it a dynamic nonprofit strategic plan example for organizations operating in fast-changing environments or seeking to accelerate their impact.

Strategic Analysis & Breakdown

The primary strength of the OKR framework lies in its disciplined focus on measurable progress toward ambitious goals. It encourages nonprofits to think beyond outputs (what we do) and focus on outcomes (the change we create), creating clear alignment from the board level down to individual programs and staff members.

Structure: An effective OKR is simple and direct:

- Objective: A memorable, qualitative statement of a major goal. For example, "Become the leading local resource for first-generation college applicants."

- KR1: Increase student workshop attendance from 200 to 350 per quarter.

- KR2: Secure partnerships with 3 new high schools by the end of Q2.

- KR3: Achieve a 90% satisfaction rate on post-workshop student surveys.

Key Advantage: OKRs decouple ambition from performance reviews. Goals are often "stretch goals," with success defined as achieving 70-80% of the Key Results. This encourages teams to aim high and innovate without the fear of failure, a crucial mindset for tackling complex social problems.

Actionable Takeaways & Adaptation

OKRs are particularly useful for translating a high-level, multi-year strategy into concrete, quarterly actions. This makes them excellent for internal management, board reporting, and communicating progress to innovation-focused funders.

For Grant Applications:

While funders may ask for a traditional annual plan, you can translate your OKRs into compelling quarterly milestones for your proposal narrative. Frame your objectives as the "goals" of the grant and use your Key Results as the specific, measurable "outcomes" you will track and report on.

Pro Tip: In grant reports, present your OKR progress transparently. Explain that achieving 70% of an ambitious goal represents significant progress and learning. This positions your organization as a sophisticated, results-driven, and honest partner.

For Resource-Constrained Nonprofits:

OKRs are remarkably low-cost to implement. Start small by defining just 3-5 organization-wide OKRs for the upcoming quarter. Use a simple spreadsheet or a free project management tool to track progress. The key is to hold regular, brief check-in meetings (monthly or bi-weekly) to maintain momentum and solve problems, ensuring the strategy remains a living document, not a binder on a shelf.

7 Nonprofit Strategic Plan Frameworks Compared

Choosing and Implementing Your Strategic Framework

We’ve explored a diverse landscape of strategic planning frameworks, from the mission-centric Theory of Change to the agile, results-driven OKR model. Each nonprofit strategic plan example serves a distinct purpose, offering a unique lens through which to view your organization's future. The journey from abstract mission to tangible impact is paved with intentional planning, and these models are the blueprints for that journey.

The core lesson from these examples is that there is no single "best" framework. The ideal choice is contextual, deeply tied to your organization's unique circumstances. A grassroots startup may find immense clarity in a simple SWOT analysis paired with an Impact-Feasibility Matrix, allowing them to prioritize high-impact, low-effort initiatives immediately. Conversely, a multi-program organization pursuing large federal grants will benefit from the robust structure of a Three-Year Rolling Plan, detailed with program-specific Logic Models that funders demand.

From Document to Dynamic Guide

The most critical mistake a nonprofit can make is treating its strategic plan as a static document, filed away after a board retreat. As we saw in the examples, the power of a strategic plan lies in its daily application. It should be a living, breathing guide that informs every decision, from program design to fundraising appeals.

Consider the following actionable takeaways to ensure your plan becomes an active tool for growth:

- Align Fundraising with Strategy: Use your plan to proactively identify grant opportunities that match your strategic goals. A well-defined plan makes it easier to say "no" to funding that, while tempting, would pull your team off-mission.

- Translate Goals into Metrics: Each strategic objective needs clear, measurable indicators of success. The Balanced Scorecard and OKR examples particularly excel at this, transforming broad goals into specific, trackable key results. This practice is essential for demonstrating impact to funders and stakeholders.

- Empower Your Team: Share the plan widely and integrate its objectives into team and individual performance goals. When every team member understands how their work contributes to the larger vision, you create a culture of shared ownership and accountability.

Making Your Plan Work for You

Ultimately, the goal is to choose and adapt a framework that provides clarity, not complexity. A plan that is too cumbersome to update or too abstract to act upon is worse than no plan at all. Start small if you need to. A one-page strategic plan that is regularly consulted and updated is far more valuable than a 50-page document that gathers dust.

By selecting the right nonprofit strategic plan example as your foundation and committing to its integration into your daily operations, you build a resilient, focused, and mission-driven organization. This strategic discipline is what separates nonprofits that merely survive from those that truly thrive. It transforms your vision into a practical roadmap, ensuring that every grant proposal written, every program launched, and every dollar spent moves you closer to achieving your ultimate mission and creating lasting change in the communities you serve.

Ready to turn your strategic plan into a powerful fundraising engine? Fundsprout helps you align your grant pipeline with your strategic priorities, manage proposal deadlines, and track reporting requirements all in one place. Transform your plan from a static document into a dynamic guide for securing the resources you need to succeed at Fundsprout.

Try 14 days free

Get started with Fundsprout so you can focus on what really matters.